This is not actually like a proper review of a chapter, instead, it is an opinionated review of what I think Jana thinks Axler thinks is important about 7.A.

Note that all of the “proofy things” in this section are poofy because problems with putting trips prior to the end of the year.

Here’s an outline:

- We defined the adjoint

- We learned some properties of the adjoint; importantly, that \((A+B)^{*} = A^{*} + B^{*}\), \((AB)^{*} = B^{*} A^{*}\), \((\lambda T)^{*} = \bar{\lambda}T^{*}\); a correlary is that \(M^{*}M\) is self-adjoint

- We defined normal, self-adjoint, and unitary

- With those definitions, we showed that eigenvalues of self-adjoint matricies are real

- Then, we created two mildly interesting intermediate results

- Over \(\mathbb{C}\), \(Tv\) is orthogonal to all \(v\) IFF \(T\) is the zero matrix

- Over \(\mathbb{R}\), \(Tv\) is orthogonal to all \(v\) and \(T\) is self-adjoint, then \(T\) is the zero matrix

- The latter of which shows that Eigenvectors of \(T\) corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are orthogonal if \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V)\) is normal

- This, all, builds up to the result of the Complex Spectral Theorem, which you should know

adjoint

Suppose \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V,W)\), we define the adjoint as a \(T^{*} \in \mathcal{L}(W,V)\) that:

\begin{equation} \langle Tv,w \rangle = \langle v, T^{*}w \rangle \end{equation}

the usual verifications could be made (setting \(w = w_1+w_2\), then applying inner product additivity, etc.) to show that \(T^{*}\) is a linear map.

properties of the adjoint

- \((S+T)^{*} = S^{*} + T^{*}\)

- \((\lambda T)^{*} = \bar{\lambda}T^{*}\)

- \((T^{*})^{*} = T\)

- \(I^{*} = I\) “identity is self adjoint”

- and, importantly, \((ST)^{*} = T^{*} S^{*}\)

All of these results are findable by chonking through the expressions for inner product properties.

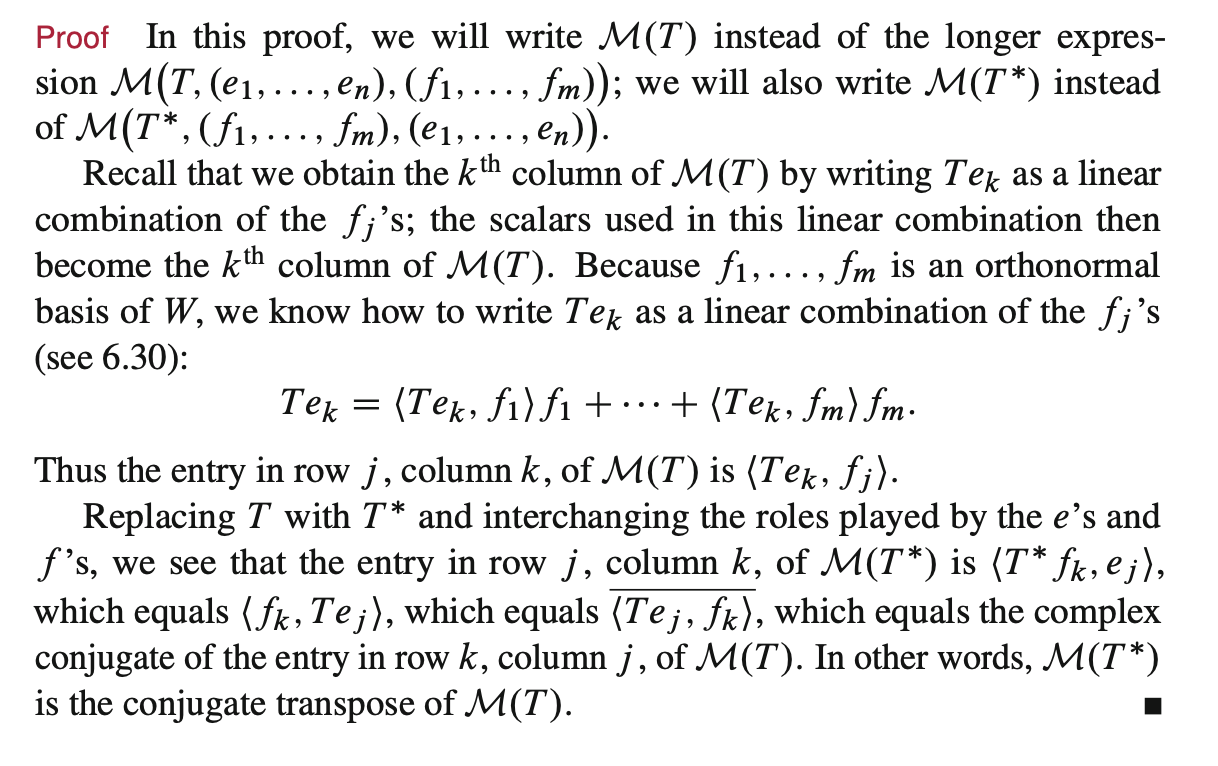

adjoint is the conjugate transpose

For complex-valued matricies, and the Euclidean Inner Product, the adjoint is the conjugate transpose of the matrix.

To show this ham-fistedly, first convince yourself that the property of \((ST)^{*} = T^{*} S^{*}\) holds for the act of conjugate transpose of matricies as well. Now, we will show how we can get to the adjoint definition from that result:

Consider:

\begin{equation} \langle v,w \rangle \end{equation}

we can represent this as the product of two “matricies”: an \(n \times 1\) “matrix” named \(v\), and a \(n \times 1\) “matrix” named \(w\); specifically:

\begin{equation} \langle v,w \rangle = v^{*} w \end{equation}

where \(v^{*}\) is the conjugate-transpose of \(v\) (the dagger is nonstandard notation, to distinguish from \(*\) the adjoint defined above which we haven’t shown yet). This is by definition of how matricies multiply and how the Euclidean Inner Product works.

So then consider the same for the above:

\begin{equation} \langle Tv,w \rangle = (Tv)^{*}w = v^{*} T^{*}w = \langle v, T^{*}w \rangle \end{equation}

Axler gives an arguably better proof involving representing the matricies w.r.t. the orthonomal bases, and then showing that the inner products just swapped slots:

Buncha matrix adjectives

And given we now know what the adjoint is, we can make some definitions:

self-adjoint

\begin{equation} A = A^{*} \end{equation}

wow.

Namely:

\begin{equation} \langle Tv, w \rangle = \langle v, T^{*}w \rangle = \langle v, Tw \rangle \end{equation}

normal

\begin{equation} A A^{*} = A^{*} A \end{equation}

As in, if the operator commutes with its own adjoint.

unitary

\begin{equation} A^{*} = A^{-1} \end{equation}

or, that \(A\) has orthonormal columns: an unitary operator is invertible, and the inverse of its atrix representation is its transpose

Eigenvalues of self-adjoint matricies are real

So, if we have:

\begin{equation} Tv = \lambda v \end{equation}

we want to show that \(\lambda\) is real. To do this, we can show that \(\lambda = \bar{\lambda}\) which would mean the \(b\) component is \(0\).

Now, recall that self-adjoint means \(\langle Tv,w \rangle = \langle v, Tw \rangle\).

Construct now: \(\lambda \|v\|^{2}\) —

\begin{equation} \lambda \|v\|^{2} = \lambda \langle v,v \rangle = \langle \lambda v,v \rangle = \langle Tv, v \rangle = \langle v, Tv \rangle = \langle v, \lambda v \rangle = \bar{\lambda} \langle v,v \rangle = \bar{\lambda} \|v\|^{2} \end{equation}

So we have \(\lambda \|v\|^{2} = \bar{\lambda} \|v\|^{2}\), which means \(\lambda = \bar{\lambda}\), as desired.

Two less important intermediate results

…that we just trust Axler’s word + our intuition for:

- 7.14: Over \(\mathbb{C}\), \(Tv\) is orthogonal to all \(v\) IFF \(T\) is the zero matrix

- 7.16: Over \(\mathbb{R}\), \(Tv\) is orthogonal to all \(v\) and \(T\) is self-adjoint, then \(T\) is the zero matrix

Why is it different? ASK JANA IDK

Eigenvectors of \(T\) corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are orthogonal if \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V)\) is normal

Prove depended on the minor results from before

and then voodo whitchcraft.

Complex Spectral Theorem

On \(\mathbb{C}\), and with \(T \in \mathcal{L}(V)\), the following statements are equivalent:

- \(T\) is normal

- \(T\) has an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors

- and so \(T\) is diagonalizable w.r.t. that orthonormal basis of eigenvectors

This proof depends on Schur’s Theorem.

The real number version requires that \(T\) is self-adjoint.

Things to ask jana

- why is 7.14 and 7.16 different