For the past 20 years, semantic indexing sucked.

For the most part, the core offerings of search products in the last while is divided into two categories:

- Full-text search things (i.e. every app in the face of the planet that stores text), which for the most part use something n-grammy like Okapi BM25 to do nice fuzzy string matching

- Ranking/Recommendation things, who isn’t so much trying to search a database as they are trying to guess the user’s intent and recommend them things from it

And we lived in a pretty happy world in which, depending on the application, developers chose one or the other to build.

There’s something really funny to do with this idea of “search”. Take, for instance, Google. Its a “search” engine—but really it recommends people information that is probably relevant; PageRank, the company’s claim to fame, isn’t even textual analysis of any type at all: it is a measure of relevance, based on centrality arguments about where the average web surfer may end up.

By framing systems like Google as an act of recommendation, we can see why it is so widely adopted: it, really, brings the best of the Internet to the user—a catalogue of sorts—based on text which the user provides as input data regarding their interest. It is, importantly, not a capital-s Search engine.

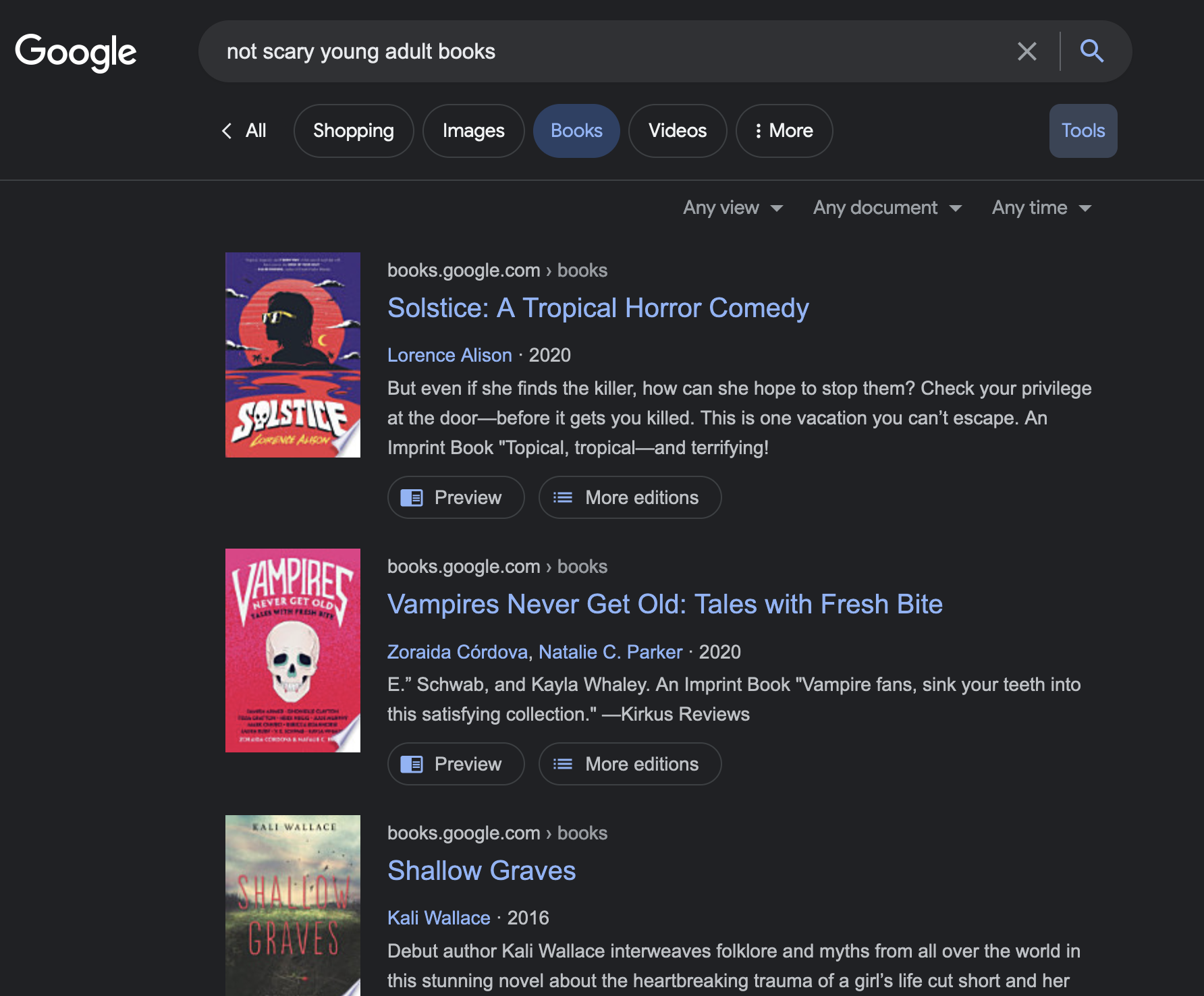

And perhaps this explains why this doesn’t work:

Figure 1: Oh my lord scary books.

Wouldn’t it be nice for a query like this to return us actual, non-scary books?

If you think about it, back in the olden days (i.e. 2019), there really isn’t a way to reconcile this difference between search and recommendation engines. Textual-based search systems were fantastically fast and gave you the exact things you needed—great for filing “that file named this”—but categorically useless when it comes to parsing large amounts of data that the user doesn’t know the exact terminology for.

Recommendation engines, on the other hand, often required special indexing or behavioral modeling for what “an average user of this type” would like, which is great for leading the user to discover certain things they wouldn’t otherwise find, but makes hilarious mistakes like the above because, well, they aren’t doing much linguistic analysis.

So, what if we can simultaneously do the guessing game for user behavior—a la “recommendation engines”—but still use a fundamentally text-based approach to perform searching—a la a “search service”?

LLMs are text matchers

Transformers are Text Matchers

Fundamentally, the Transformer (the basis of all of those lovely large-language models (LLMs)) is a “sequence transduction model”—they are (and were originally invented as) a translation model of sorts. And I find it easy and productive to think of LLMs in that mindframe: although their output may look like human-like “reasoning”, LLMs’ fundamental job is to match one bit of text (context) against another (output).

LLMs are Internet Text Matchers

The actual thing that is making the whole of the world go crazy right now, though, is the fact that LLMs, transformers trained on the internet, seem to be able to handle text-to-text “translation” tasks of a much more general nature:

- “given a food, translate it into its recipe”

- “given this text, translate it into the same written with a pirate voice”

- “given the comment, translate it to the code that follows”

You see, instead of carefully supervised translations a la the original Transformer, GPT+friends is simply chopping off the entirety of the input encoding process and letting the decoder ramble on its own. Hence, its outputs are functionally text matches of the context against the training data: that is, these LLM models effectively are text-matchers between the whole of the internet and your input.

And hence, the promise

Let’s recap real quick.

- Transformers are text matchers

- LLMs, which are transformers, are text matchers against the text on the internet

And here’s the corollary to both of these statements:

- Transformers match text

- LLMs, which are transformers, is trained (and biased) towards the things people would typically be looking for on the internet

That is, though LLMs fundamentally match text, they know what’s on the internet and how people talk about (and try to look for) them.

The point above is, to me, a very profound idea. LLMs essentially achieve what we were hoping to edge towards in the last 20 years—closing the gap between recommendation (what people want) and search (text matching) systems into one uniform interface.

And, praise be, LLMs seems to be highly directable at this task as well: they excel at few-shot and zero-shot training tasks; meaning, if you just give the Transformer a few examples of how to “translate” a piece of its input, it will happily do it with some accuracy following your example.

Aside: Stop Building Gosh Darn Chatbots

Fortunately, people not named yours truly has also noticed these exciting capabilities of LLMs.

What confuses me, though, is the fact that everybody and their pet duck is building a chat bot or “answering” service of some description: capitalizing on the fact that LLMs have trained knowledge of text on the internet, but completely disregarding the fact that LLMs fundamentally are best at “matching” existing text in its context and not hallucinating new text—as these “answer services” want to do.

What gives? Wattenburger has this fantastic take on why chat bots are not the best interface for LLMs. To me, the most salient observation—one which stems from her wonderful arguments about chat bot’s poor observability and iteration cycle—is that the generated text from these current LLM “search” services (called “retrial augmented generation”) is just so darn long.

When we look information on a site like Google, I believe our goal is generally to shove the desired information in our head as quickly as possible and know where we can go to learn more; if we wanted to read a 300 word summary about it (as Perplexity AI, Mendable, Phind etc. is want to give us) we can just go look up the source ourselves.

To me, the duty of a search platform, LLM or not, is to get the user on their merry way as quickly as possible—information in head or link in hand—not for the user to navigate a possibly-hallucinated rant about the topic they are looking for, followed by 3 source citations.

Making a LLM Search Engine

And so we face a rather daunting task. To make a better search service with LLMs, we have to:

- Leverage LLM’s fantastic text matching capabilities

- Allow LLMs to inject their trained biases into what’s relevant to the user in order to act as a good recommendation engine

- Do so in as little words as possible written by the LLM

These three bullet points has consumed much of my life for the past 6 months, culminating in a reference implementation of such a “LLM search engine” called Simon. Let me now tell you its story.

Fulfilling a search query, Part 1/3

Our first goal is to figure out