“Doing NSM analysis is a demanding process and there is no mechanical procedure for it. Published explications have often been through a dozen or more iterations over several months” — (Heine, Narrog, and Goddard 2015)

Approach and XD

Introduction and Theory

The Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM) approach (Wierzbicka 1974) is a long-standing hypothetical theory in structural semantics which claims that all human languages share a common set of primitive lexical units—usually words, but, in some languages, short connected phrases—through which all other words in each language can be defined.

For NSM to hold, two main results must be demonstrated. (Heine, Narrog, and Goddard 2015) The theory’s validity hinges, first, upon the existence of semantic primes—a series of primitive lexical units both indefinable via other words in the same language but also is universally lexicalized across all languages. Second, the theory’s confirmation requires the ability to perform “reductive paraphrasing”, the process of defining all other words in a language with respect to the universal semantic primes’ manifest in that language.

If proven as fact, the NSM theory and its implications has reaching implications into the long-standing (footnote: not to mention often personally fierce) conflict between the newer theories of generative semantics—where structure of language is created in support of meaning—and Noam Chomsky’s transformational generative syntax—where meaning is filled to precomputed structure, which NSM suggests (Harris 2021).

The difficulty of forming adequate investigations in the area of NSM is due the theory itself being exceedingly hard to falsify—the principle method through which NSM is demonstrated is via the manual (i.e. non-standardized) lexicalization of semantic primes and a partial demonstration of their relations (Geeraerts 2009) to other words in the language. Whenever one irregularity in the theory is identified (Bohnemeyer 1998), the proponents of the theory simply respond with another update to the (non standardized) set of reductive paraphrasing rules to account for the irregularity (NO_ITEM_DATA:goddard1998bad.)

Yet, there are repeated empirical (again, non-standardized) confirmations of the existence of the original set (Wierzbicka 1974) of semantic primes in other languages (Chappell 2002; Peeters 1994; Travis 2002); there are also numerous demonstrations of the proposed applications (Goddard 2012) of the theory in structural semantics. These facts has therefore maintained the relevance of NSM in current linguistic study but rendered the theory without a very clear path forward. Due to this reason, recent research has placed larger focus on functional (cognitive linguistical) theories (Divjak, Levshina, and Klavan 2016) and largely overlooked structuralist arguments like the NSM.

Broad Goals and Approach

To complement the very large body of work already in the identification of semantic primes for NSM in numerous languages, we aim in this project to investigate the process of reductive paraphrasing to provide a baseline evaluation of the feasibility of NSM as a theory. The approach proposed below is intended to very generally test the practicality of the act of reductive paraphrasing from the published set of primes: whether paraphrasing from those primes is even broadly possible across the entire lexicon of the few languages for which it is purported to be possible. This test remains needed because, quite counter-intuitively, metalanguage theorists have been constructing lexicalizations for non-prime words on an “as-needed” basis such as in (Wierzbicka 2007). No lexicon-wide demonstrations of lexicalizability has been performed (i.e. reductive paraphrasing all words down to the primes) as the current approach of manual definition of words from primes is significantly time-consuming and requires careful consideration of NSM’s semantic grammar between primes.

We aim perform a lexicon-wide test of reductive paraphrasing computationally via much newer approaches in computational linguistics, specifically model-based Natural Language Processing (NLP).

In order to isolate the exact problem of reductive paraphrasing, we first will have to highlight a few key assumptions by the NSM theory and therefore this project.

The semantic metalanguage theory is itself built on the assumption that “each language is its own metalanguage” (Goddard 2002)—that human languages are broadly lexicalizable by itself (i.e. one can write an English dictionary by only using English.) We believe that the examination of this assumption is not within scope of the study and—given it is fairly universally true from a practical standpoint (i.e. English dictionaries exist)—we will take it as fact. We will use this fact further as the control for the feasibility of the approach, as discussed in the section below.

The remaining assumptions of NSM to be tested here, then, is that 1) semantic primes exist and 2) the original set of NSM primes published (Wierzbicka 1974) (and in subsequent studies in various other languages highlighted before) are correct and, through reductive paraphrase, can lexicalize every word in the lexicon.

Aims and Experimental Design

In this study, we aim to develop a computational protocol for lexicon-wide testing of the possibility of performing reductive paraphrasing for every word in the lexicon given a set of purported semantic primes. Practically, this means that we are trying create a model to test whether all words in a language is lexicalizable when restricted to only using a chosen subset of primes in the same language.

To create a truly replicable test for lexicalizability under restriction, we turn to probabilistic NLP approaches. We propose the following metric for lexicalizability: a word is “lexicalizable” under some set of semantic primes if there is a lossless mapping between a linear combination of the primes’ latent embeddings to the word in lexicon space.

Under this model, all words in the lexicon are lexicalizable by the set of primes being tested if there is a lossless projection of the bases of the lexical space to the primes’ latent embedding space.

That is, given we have a latent embedding space of \(n\) semantic primes \(P^n\) and some lexicon \(W\) with \(m\) words, we aim to identify a linear mapping \(M\) such that:

\begin{equation} Mp = e_{W_j}\ |\ p \in P^n, \forall j=1\ldots m \end{equation}

where, \(e_{W_j}\) is the \(j\) th standard basis of \(W\) (i.e. \(j\) th word in the lexicon.)

This projection is not, in principle, impossible. In the high-dimensional space of the entire lexicon, individual lexicalized words represent only the basis vectors of the space (and indeed in one-hot encodings for deep learning they are shown as the standard-basis of the lexicon-wide space.) Whereas in the lower-dimensional subspace of primes, a linear combination of primes can be used to represent each lexicalized word in the full lexicon.

Success in identifying a feasible \(M \in \mathcal{L}(P, W)\) for a given \(P\) and \(W\) indicates the feasibility of finding a linear combination in \(P\) which maps to all \(w \in W\), which means reductive paraphrase of \(w\) to a set of primes in \(P\) is possible as there is a direct “translation” (namely, \(W\)) from \(P\) to \(W\).

To actually compute \(W\) given \(P\) and \(M\), we leverage the well-established Transformer encoder-decoder architecture for language modeling (Vaswani et al. 2017). Furthermore, we frame the problem as one of unsupervised multi-lingual translation without alignments.

The basis of the model proposed to be used to obtain \(W\) is (Artetxe et al. 2018), a unsupervised multi-lingual translation model.

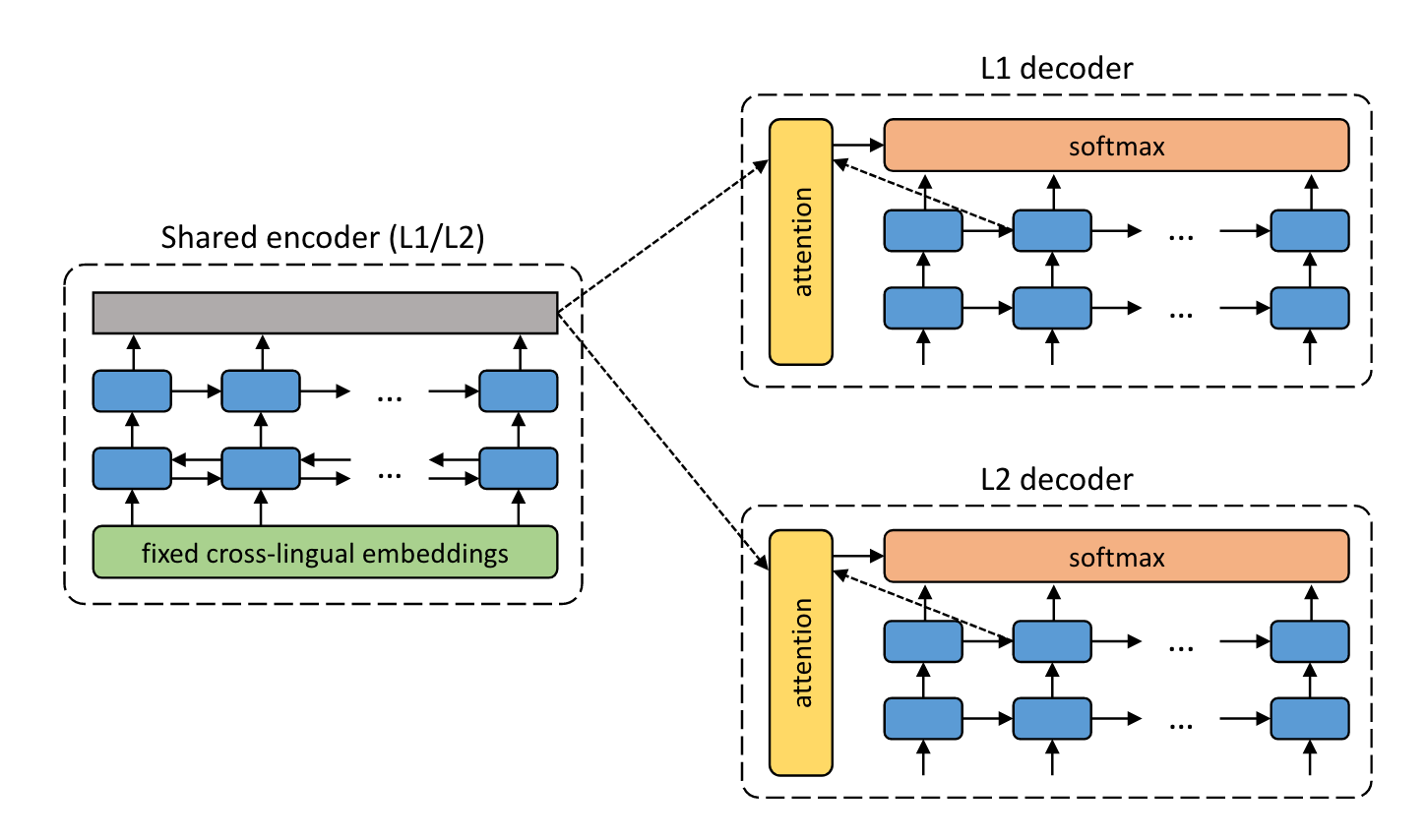

Figure from (Artetxe et al. 2018).

Figure from (Artetxe et al. 2018).

As we are performing the task with word embeddings, not sentences like that of (Artetxe et al. 2018), the cross-attention lookup vector will serve no purpose (be \(0\)) (Niu, Zhong, and Yu 2021) and hence removed.

For the sake of standardization, we will call \(P\) the primary language/lexicon \(L1\), and \(W\) the second language/lexicon \(L2\). The basic hypothesis provided by (Artetxe et al. 2018) is that, through alternating samples of \(L1\) and \(L2\) through the model against their corresponding decoders using a shared encoder and separate decoders, the shared encoder is trained to perform the task of autoencoding for both lexicons at once. Therefore, at prediction time, to get the “translation” of an input, one simply applies the decoder of the desired lexicon to obtain a result.

During training, the input to the shared encoder can either be a word from either \(P\) or $W$—sampled with equal probability. If the input is from \(P\), we connect the output of the shared encoder with the \(L1\) decoder and train with the objective of recovering the input. Essentially, we are using the model as a alternate method of training a variational auto-encoder (Klys, Snell, and Zemel 2018) with alternating decoders given the lexicon being analyzed.

This task is trivial if the embedding space after the shared encoder is exactly as wide as both lexicon. However, we will restrict the output dimension of the shared encoder to \(dim(P)\) which after training we will call the latent embedding space of \(L1\); this name is verified and justified as a part of the feasibility check below.

We will also use the backtranslation mechanism proposed by (Artetxe et al. 2018) during training: whereby the autoencoded output from \(L1\) is used as target for the same input as \(L2\) (as well as the reverse), mimicking the process of translation.

After training, the \(L2\) decoder would then be the candidate \(W\), mapping from the (proposed) latent embedding space of \(P\) to the lexicon \(W\).

Following both (Artetxe et al. 2018; Conneau and Lample 2019) we will use cross-entropy as the objective function of training.

Feasibility Checkpoint

We first need to show that, as expected, the model architecture proposed above—upon convergence—will create a latent embedding for \(L1\) after encoding if the output size for encoding is \(dim(L1)\) (defined to be equal to \(dim(P)\)).

A trivial test of whether the encoding output is desirably the embedding space of \(L1\) is that, through training with a toy mapping \(P=W=L1=L2\), we would expect both decoders to be an one-to-one mapping that simply copies the input. That is, after training with \(P=W\), we should see that activating one input in the shared post-encoding space should activate one or close to one feature only in both decoder’s output space.

Numerically, this means that the result obtained from taking the mean entropy of both outputs given a singular input activation should be statistically insignificantly different from \(0\).

That is, we expect that given trained decoders \(L_1\) and \(L_2\), and standard bases of \(W=P\) named \(e\), we should see that:

\begin{equation} \frac{\log(L_1e_j) + \log(L_2e_j)}{2} \approx 0: \forall j = 1\ldots dim(W) \end{equation}

We expect this result because, through gradient-descent, the quickest minima reachable to capture variation in the input perfectly is the copying task; therefore, we should expect here that if the post-encoding distribution is the same distribution as the input, the model’s decoders will fit to the copying task. If the post-encoding distribution is different from the input, the model’s decoders would then have to actually perform nontrivial mappings to achieve the desired autoencoding result.

Checkpoint 2 + Hypothesis 1

The following is the first novel result that we can show with the new architecture. We first hypothesize that the model should converge when training to the target of the (already linguistically accepted, as aforementioned) result that English words are themselves a metalanguage.

For \(dim(W)\) iterations (similar to (Webb et al. 2011)), we will leave a word chosen at random out of the lexicon of \(P\). This operation results in \(dim(P) = dim(W)-1\). We will then train the model until a local minima is reached and measure convergence.

To test this hypothesis, we will measure the cross-entropy performance of \(L2\) decoder upon the word that is left out. The resulting loss should be statistically insignificantly different from \(0\) if the word is successfully lexicalized via the \(dim(W)-1\) other words not left out in \(P\) in the latent embedding space after encoding.

If the hypothesis is not successful, the model cannot converge even on a large subset of the entire lexicon, much less in the limited subset of the 60-word NSM-proposed metalanguage; it is therefore imperative not to continue the study unless convergence at this point can be shown. Importantly, however, failures in this step does not show any claims about reductive paraphrasing as we are simply benchmarking the model against a control linguistic assumption we discussed earlier.

In any case, it would be valuable at this point to again perform analyze for post-encoding output to observe any reductive paraphrasing behavior.

Hypothesis 2

At this point, we will set the lexicons to the sets we are actually testing. We will set \(P\) to be the list of semantic primes established by (Heine, Narrog, and Goddard 2015), and \(W\) to the English lexicon.

Should lexicalization of all of the English lexicon via the semantic primes only be possible, this model should again converge after training with cross-entropy inappreciably different from \(0\). This result would indicate the existence of a \(W\) (i.e. \(L2\) decoder), indicating the possibility of lexicon-wide reductive paraphrasing.

Institution and Experience

The actual protocol proposed as a part of this study (namely, creating, training, and calculating metrics from the autoencoder) is a technical concept taught as a part of the regular curriculum of Advanced Machine Learning at Nueva; however, expertise and mentorship may still be required when implementing a complex model topology and training mechanism like the one proposed. The open-ended project structure of the Advanced Machine Learning course supports and sometimes necessitate implementing a model like the one proposed with the help of the CS faculty. Therefore, if additional mentorship is indeed required, there exists support available within the institution.

The more difficult skill-set to capture is the knowledge regarding the theories of NSM and the field of structuralist linguistics in general. As of writing, we are not aware of any students which has an active research interest in traditional linguistics; however, this knowledge constitute a far more insignificant portion of the actual mechanics of the project and is more importantly very easily taught. Mentorship is also available here from members of the Mathematics and CS faculty with prior research interest in computational linguistics.

In terms of equipment, the most important tool required in working with a large-scale neural network is a matrix-mathematics accelerator; this often takes the form of a consumer graphics card and typical desktop computing setup. For the Machine Learning course taught at Nueva, Google’s Colab (and their free graphics card addition) is frequently used to address this need and would at a minimum suffice here. Also, it is based on the personal experience of the author, though by no means definite, that a large selection of students at Nueva has comparable hardware for training available at home.

Provided network access to the computing accelerator, this experiment can be done under any setting and definitely does not necessitate the use of the biology lab.

Impact

Academic Significance

Within the short term, this experiment provides two major results. First, it establishes the use of a bifercated unsupervised encoder-decoder translation model like that proposed by (Artetxe et al. 2018) as a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) (Klys, Snell, and Zemel 2018) with the ability to define and train the hidden latent representation after encoding. Although traditional CVAEs are frequently more suited for most output-aware generation tasks, this new scheme supports the direct influence of the latent representations of the encoder instead of using an additional input to both the encoder and decoder to influence such representations, like in traditional CVAEs. This difference is significant for as it creates the where dimensional projection is needed but the content of the latent representation itself is also relevant to the study.

Of course, the short-term result also includes the direct result of the second tested hypothesis: a systemic, lexicon-wide evaluation of the feasibility of reductive paraphrasing. The study is to develop a computational protocol for lexicon-wide reductive paraphrasing by creating a lossless mapping between a linear combination of the primes’ latent embeddings to the word in lexicon space.

If both initial metrics succeeds and the third, final reduction step with actual semantic primes fail, the result would indicate an inability to create such a lossless mapping, and therefore raise concerns about the lexicon-wide applicability of the reductive paraphrasing on the set of published semantic primes. That, there is not even a locally convergent linear combination of primes that will generally describe all of the lexicon, despite the hypothesis by NSM theorists. This result will be highly impactful for NSM theory in general which necessitates the possibilty of reductive paraphrase (Geeraerts 2009) (Vanhatalo, Tissari, and Idström, n.d.).

On the long term, demonstrations of reductive paraphrasing has wide-reaching implications into NSM theory is general (Heine, Narrog, and Goddard 2015; Geeraerts 2009), and the field of language learning. The paraphrasing capacity of the proposed embedding would hypothetically be able to create a semantic mapping between a set of words to one other word; in this way, it is not infeasible to create a language-learning tool with continually larger embedding size to slowly create a larger lexicon in the target user. Early results (Sharma and Goyal 2021) have shown a possible application of such an approach, using supervised machine translation techniques.

Learning and Teaching

One to two students, along with a facilitator, would be an ideal size for this experiment. Primarily, the three main roles will include model engineering, training and validation, and model ablation and testing. The last role requires the most amount of traditional linguistics knowledge as the student’s role would be to connect the weights in the model to the applicable theories being tested.

The study proposed is an extremely conventional empirical Machine Learning/NLP study. From a pedagogical standpoint for XRT, this study will be a diversion from the traditional wet-lab sciences or survey-based educational/social sciences commonly produced by the lab and lead a new avenue for the Lab’s expansion. Within Nueva, empirical research into machine learning is frequently done through independent study or the Intro/Advance machine learning courses—which were recently expanded due to widening interest at the Upper School.

Participation in this project provides its constituent students an opportunity to practice publish-quality ML/NLP in a longer-term and multi-stage project previously not possible through semester-long courses. Students are trained to perform model construction, data selection and cleaning, collection of model validation metrics, as well as model ablation and interpretation: important concepts in ML operations taught but not formalized in the Machine Learning course as the course exercises, while open-ended, isolate only one skill and have expected outcomes.

Given the demand and rate of student progression between Intro/Advanced courses in ML each year, developing a suitable approach to propagate true machine-learning research will be relevant to upwards of 30 students each year.

Incidentally, students also get an exposure to the practice of conventional linguistics and the new trend of applying empirical research NLP back against classic semantics; however, the demand for this exact skill is likely small at Nueva.

Though the tool used and expanded upon by this experiment is applicable to the NLP research community, it is unfortunately difficult to predict its future applications to XRT or Nueva students without seeing more expansion into the area of ML and NLP by the XRT lab.

Safety and Ethics

The following are the responses to the safety and ethics checklist.

- This project does not satisfy any triggers of the second-expert protocol. All data needed is from a dictionary (for the English lexicon, e.g. (Fellbaum 2010)) as well as the semantic primes listed in a figure on the article (Heine, Narrog, and Goddard 2015). The data is being generated during compute.

- The actual compute hardware will need to be stored in either in the cloud (not on-prem), physically in the iLab, or (for personal compute hardware), in students’ homes. An internet connection and a model training acceleration scheme (such as the free Google Colab) would suffice.

- None foreseeable

- See below

- The experiment is done on the English lexicon. It is difficult to imagine a tangible harm from the experiment.

- This study provides students with an opportunity to conduct a full research study in ML; XRT has not had this from of projects before and approval would result in a new avenue of research being conducted with XRT. However, if the project is not approved, other ML projects may subsequently surface and students can leverage those opportunities to learn about the practice of empirical ML instead.

As with most machine-learning projects, it is customary and appropriate to end with a statement on ML ethics and its implications. This study is a linguistics, lexicon-scale study, and the data sourced is available generally and not subject to copyright or any known data-protection laws. The inputs to the model are combinations of English words, and the model produces singular English words. The benefits of this model involves generating new knowledge about the English lexicon and semantic theories. The only known harm of the model involves the mis-intepretation of its results, creating overreaching generalizations to semantic primality analysis or NSM theories. The model and source code can be released to the general public without broad impact.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Brandon Cho at Princeton University and Ted Theodosopoulos at The Nueva School for the very interesting discussion/argument that resulted in this proposal almost a year ago. I would like to thank Klint Kanopka at Stanford University for his mentorship and discussion of the overall feasibility of the approach and pointing out the path that lead to the proposed model’s basis in machine translation. Finally, I would like to thank Prof. Brian MacWhinney at Carnegie Mellon University for pointing out discourse between structuralism/functionalism during our exchanges and for his mentorship in my exploration of computational linguistics.