Chapter 3

Problem 3.10

Part a

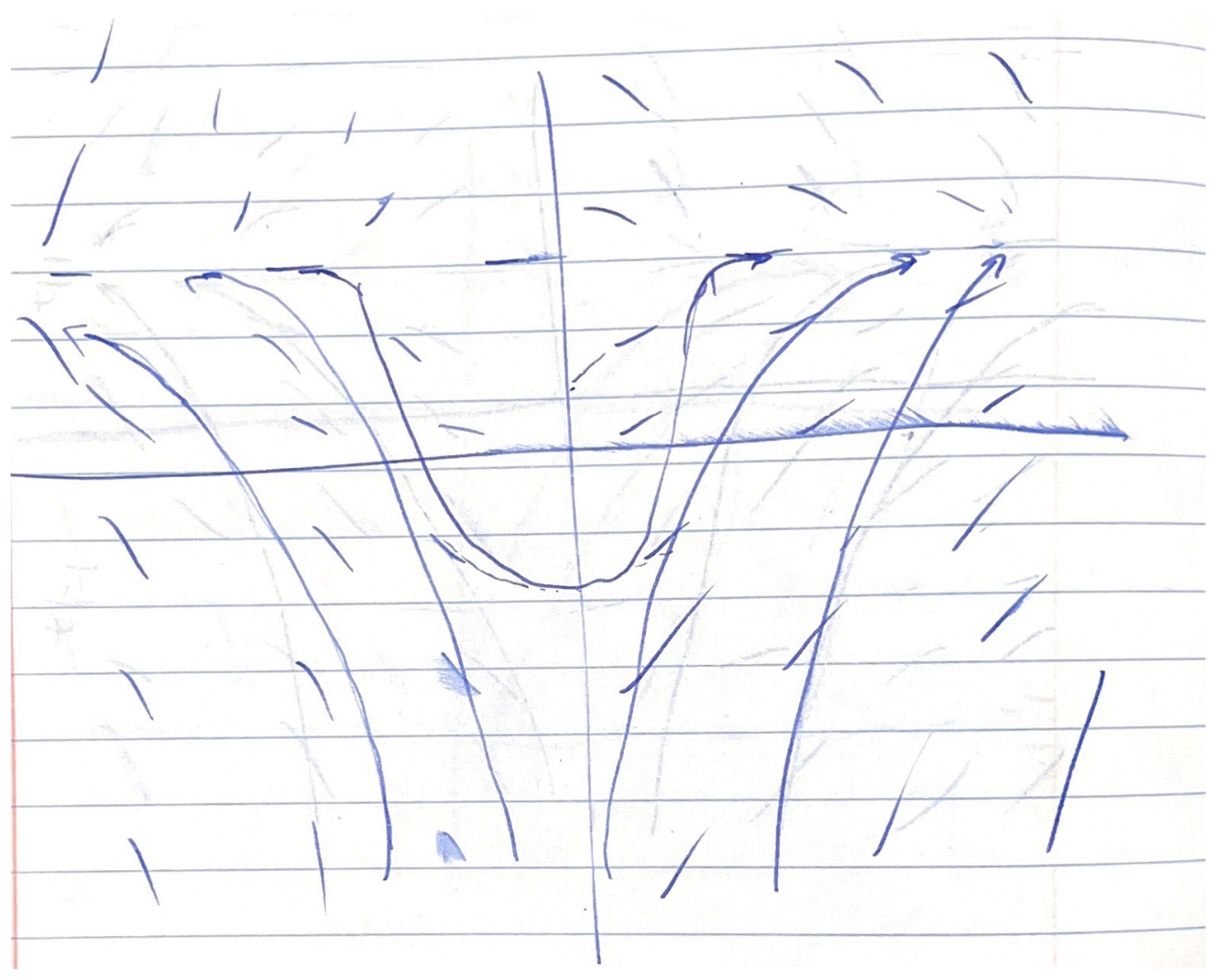

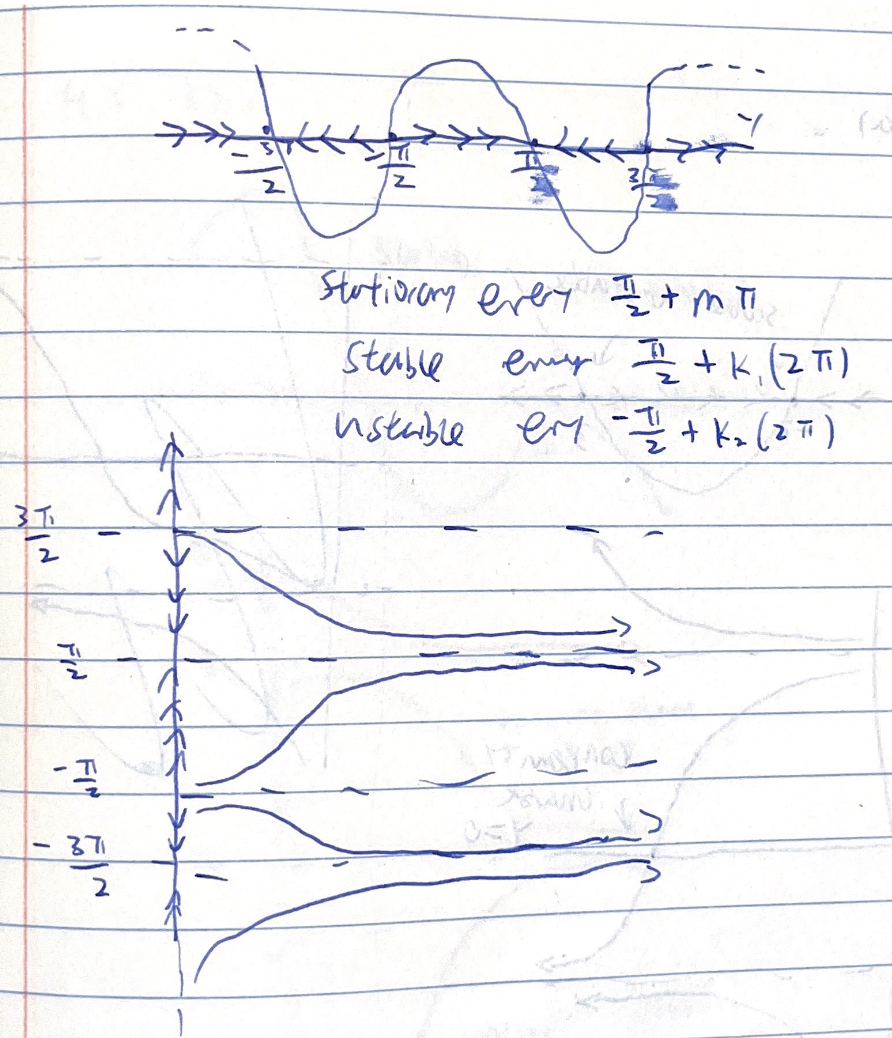

Notably, the slope field is symmetric across the \(y\) axis, and repeats with every \(m\pi\) interval about the line \(\frac{\pi}{4}\).

Part b

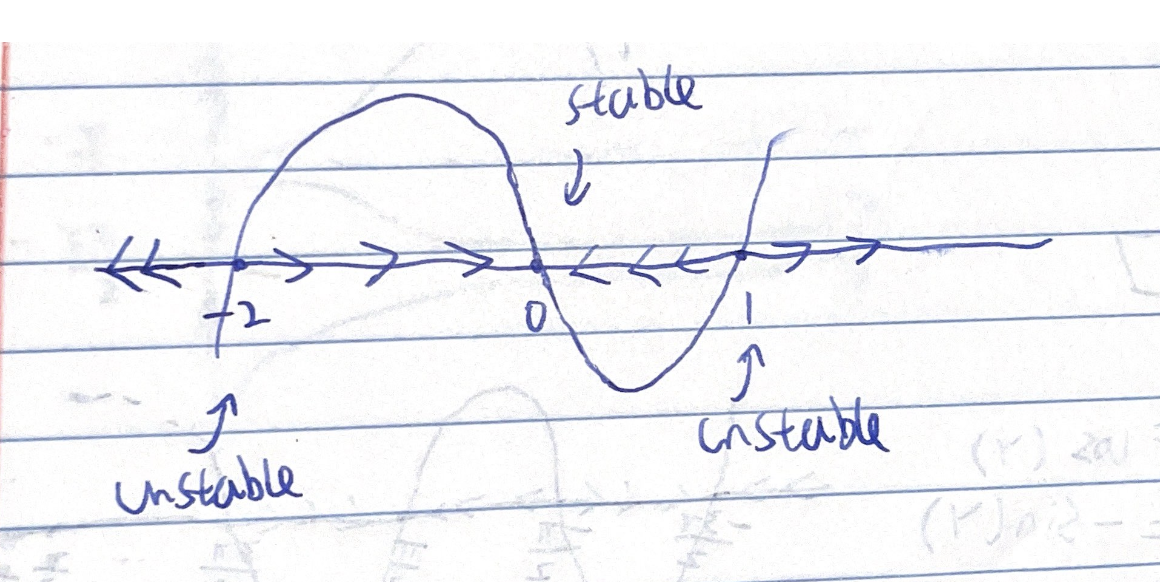

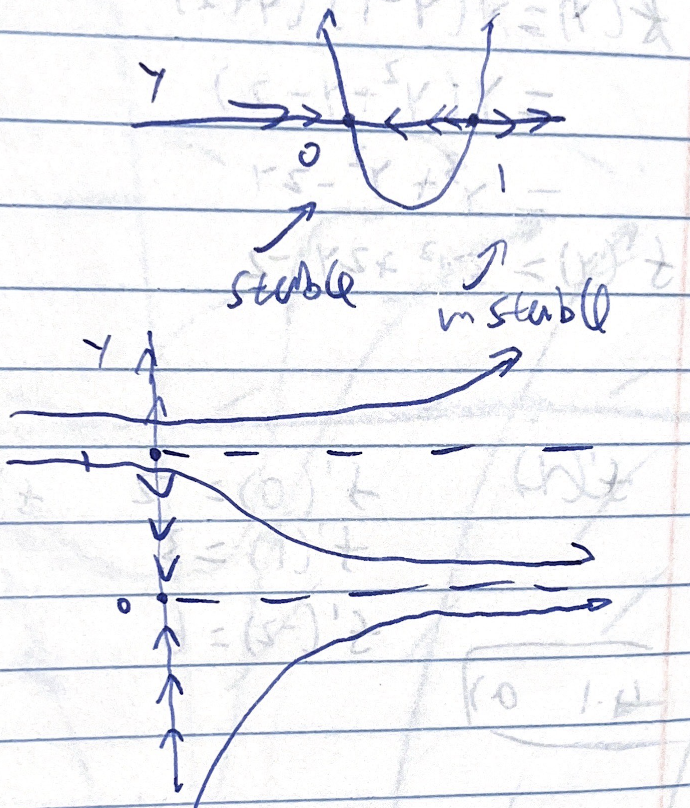

We have a stationary value at \(y = \frac{\pi}{4}\). Beyond that, as initial \(x>0, y<\frac{\pi}{4}\), solutions will all trend towards \(y=\frac{\pi}{4}\) as \(t \to \infty\), because the derivative is positive for that entire region. For \(x>0, \frac{\pi}{2}>y> \frac{\pi}{4}\), the function will also trend towards \(\frac{\pi}{4}\), as the slope is negative for that entire region. This pattern repeats for all \(y_0+m\pi\). That is, for instance, for \(y\) between \(m\pi+\frac{\pi}{4} < y < m\pi + \frac{\pi}{2}\), \(y\) will trend towards \(m\pi + \frac{\pi}{4}\). For initial \(t<0, y < \frac{\pi}{4}\), most solutions will trend towards \(-\infty\) as the region has negative slope. Yet, as \(t_0 \approx 0\), the function will never hit the singularity point of \(y = -\frac{\pi}{2}\) before traveling to the \(t>0\) side, resulting in it trending towards \(+\infty\). Finally, for initial \(y>\frac{\pi}{4}, t<0\), the function will reach \(+\infty\) because it will hit the positive singularity at \(\frac{\pi}{2}\).

Chapter 4

Problem 4.1, part a

Problem 4.2

Part a

Part b

Problem 4.3

Part a

Part b

Problem 4.7

Part a

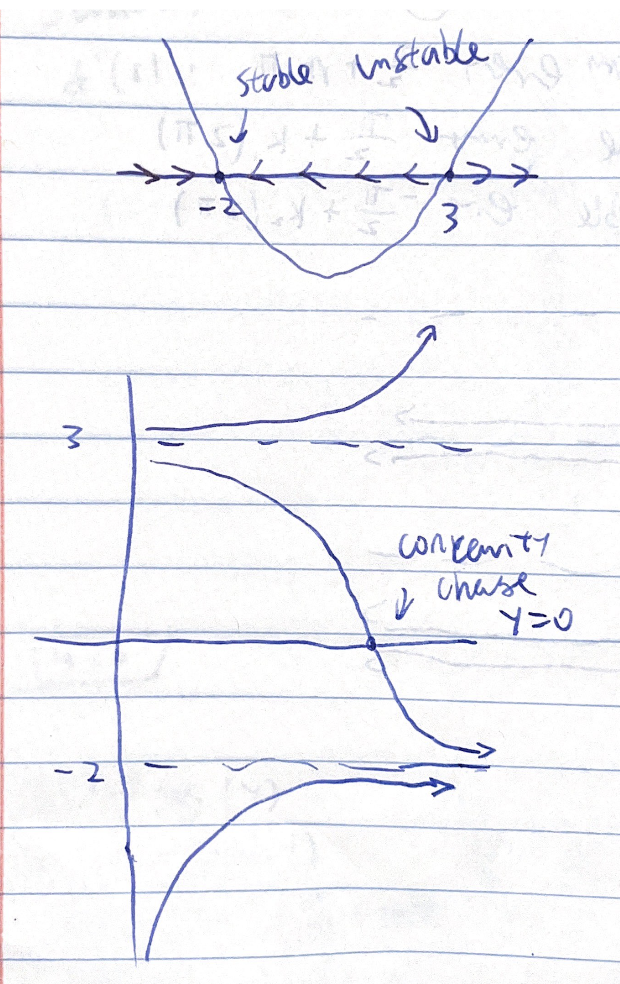

We have:

\begin{equation} \dv{V}{t} = rV \ln \qty(\frac{K}{V}) \end{equation}

We see that when \(V=K\), we have \(\ln(1) = 0\) on the right hand side, meaning \(K\) is a stationary value.

Now, we desire that this value is unique in the positive half-line; so, for \(V > 0\), we have \(0 = rV \ln (\frac{K}{V})\), and we desire \(V=K\) exactly. Note that \(V=0\) would not work, because \(V>0\). Therefore, we now have:

\begin{equation} \ln (\frac{K}{V}) = 0 \end{equation}

meaning \(\frac{K}{V} = 1\). Finally, we have \(V=K\), as desired.

Importantly, note now that:

\begin{align} \dv V rV\ln (\frac{K}{V}) &= r(\ln \qty(\frac{K}{V}) + V \qty(\frac{V}{K}\cdot\qty(K(-1)V^{2})) \\ &= r \qty(\ln\qty(\frac{K}{V}) - V\qty(\frac{1}{V})) \\ &= r\qty(\ln \qty(\frac{K}{V}) -1) \end{align}

Now, we see at \(V=K\), this expression yields \(r(0-1)\), meaning \(-r\). As we have \(r>0\) given in the problem, we see that the stationary value is stable.

Part b

We again have:

\begin{equation} \dv{V}{t} = rV\ln \qty(\frac{K}{V}) \end{equation}

that is:

\begin{equation} \dv{V}{t} = -r V \ln \qty( \frac{V}{K}) \end{equation}

Taking an integral on both sides using the division method:

\begin{equation} \int \frac{1}{V\ln \qty(\frac{V}{K})} \dd{V} = -\int r \dd{t} \end{equation}

Now, let us treat:

\begin{equation} u = \ln \qty(\frac{V}{K}) \end{equation}

we note that \(\dd{u} = \frac{1}{V} \dd{V}\).

Hence:

\begin{equation} \int \frac{1}{u} \dd{u} = -rt +C \end{equation}

therefore:

\begin{equation} \ln (u) = -rt+C = \ln \qty(\ln \qty(\frac{V}{K})) \end{equation}

Now, this means that:

\begin{equation} \ln \qty(\frac{V}{K}) = Ce^{-rt} \end{equation}

Plugging in our initial conditions at \(t=0\), we have:

\begin{equation} \ln \qty(\frac{V_0}{K}) = C \end{equation}

Substituting that in, we have:

\begin{align} \ln \qty(\frac{V}{K}) &= \ln \qty(\frac{V_0}{K})e^{-rt} \\ &= \ln \qty(\qty(\frac{V_0}{K})^{e^{-rt}}) \end{align}

Finally, then, we see that:

\begin{equation} \frac{V}{K} = \qty(\frac{V_0}{K})^{e^{-rt}} \end{equation}

which means:

\begin{equation} V = K\qty(\frac{V_0}{K})^{e^{-rt}} \end{equation}

as desired.

Part c

We want to perform the inverse operation of the previous question.

\begin{equation} V(t) = K\qty(\frac{V_0}{K})e^{-rt} \end{equation}

Now, that means that:

\begin{align} V’(t) & = K \qty( \frac{V_0}{K})^{e^{-rt}} \ln \qty(\frac{V_0}{K}) \qty(e^{-rt}(-r)) \\ &= -rk \qty(\frac{V_0}{K})^{e^{-rt}} \ln \qty(\frac{V_0}{K}) e^{-rt} \\ &= -r v(t) \ln \qty(\qty(\frac{V_0}{K})^{e^{-rt}}) \\ &= -r v(t) \qty(\frac{V}{K}) = r V(\frac{K}{V}) \end{align}

as desired

Part d

Problem 4.10

Part a

When the right side of the ODE “vanishes”, we have:-

\begin{equation} ax \qty(1- \frac{x}{b}) - \frac{x^{2}}{1+x^{2}} = 0 \end{equation}

which means:

\begin{equation} x\qty(a \qty(1- \frac{x}{b}) - \frac{x}{1+x^{2}}) = 0 \end{equation}

Now, we have that \(x = c > 0\), meaning \(x\neq 0\). Hence, for the top to hold, we have:

\begin{equation} a \qty(1- \frac{x}{b}) - \frac{x}{1+x^{2}} = 0 \end{equation}

Meaning:

\begin{equation} a \qty(1- \frac{x}{b}) = \frac{x}{1+x^{2}} \end{equation}

that is, the graphs of \(a \qty(1- \frac{x}{b})\) and \(\frac{x}{1+x^{2}}\) intersect, as desired.

Part b

We know that solutions to the expression given in part a), that

\begin{equation} a \qty(1- \frac{x}{b}) = \frac{x}{1+x^{2}} \end{equation}

are the only locations where positive stationary values exists. Visually, if \(a(1-\frac{x}{b})\) is below the location at \(x = \sqrt{3}\), and the function increases as \(x\) decreases, we know that the function is bound to intersect at one point only with the curve of \(\frac{x}{1+x^{2}}\) given which is concave down at values \(x<\sqrt{3}\). We know this intersection point is positive because at \(x=0\), which is where the visualized graph of \(\frac{x}{(1+x^{2}}\) changes signs, we have \(a(1-\frac{x}{b}) = a\), and we have \(a > 0\).

Part c

If the functions cross, the left term will start out before crossing being large than the right term (because its cross “from above”, visually). This means that prior to the stationary point, the ODE’s right hand side is positive. After crossing, the situation in b) gives that the RHS of the ODE is negative now as the second term is given to be larger than the first term.

This means that the stationary point is an attractor (positive slope coming from below, negative slope coming from above), so it is stationary.

Chapter 5

Problem 5.2, Part b

LHS:

\begin{equation} (2+3i)(4-i) = 8 - 2i + 12i +3 = 11 + 10i \end{equation}

\begin{equation} (11+10i)(1-i) = 11 -11i+10i + 10 = 21 - i \end{equation}

RHS:

\begin{equation} (4-i)(1-i) = 4 -5i -1 = 3 - 5i \end{equation}

\begin{equation} (2+3i)(3-5i) = 6 - 10i + 9i +15 = 21 -i \end{equation}

and finally:

\begin{equation} 21-i = 21-i \end{equation}

Problem 5.3, Part c

\begin{align} \frac{1-11i}{1-i} &= \frac{1-11i}{1-i}\frac{1+i}{1+i} \\ &= \frac{1+i-11i+11}{1+1} \\ &= \frac{12 -10i}{2} \\ &= 6 - 5i \end{align}

Problem 5.5, Part c

\begin{align} \qty | \frac{8-i}{4+7i}| &= |8-i|/|4+7i| \\ &= \sqrt{\frac{64+1}{16+49}} \\ &= \sqrt{ \frac{65}{65}} \\ &= 1 \end{align}

Problem 5.6

Part c

We have:

\begin{equation} (3+i)(2+i) = (5 + 5i) \end{equation}

Writing it in polar form gives:

\begin{equation} \sqrt{50}e^{i \arctan (1)} = \sqrt{50}e^{i \frac{\pi}{4}} \end{equation}

Now, we have:

\begin{equation} (50)^{\frac{1}{4}} e^{i \frac{\pi}{8}} \end{equation}

Finally, writing this out in rectangular gives:

\begin{equation} (50)^{\frac{1}{4}} \qty(\cos \qty(\frac{\pi}{8}) + i\sin \qty(\frac{\pi}{8})) \end{equation}

Recall now that:

\begin{equation} \sin \frac{x}{2} = \sqrt{\frac{1- \cos x}{2}} \end{equation}

and

\begin{equation} \cos \frac{x}{2} = \sqrt{\frac{1+ \cos x}{2}} \end{equation}

Finally, that:

\begin{equation} \sin \frac{\pi}{4} = \cos \frac{\pi}{4} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \end{equation}

Now, notice that:

\begin{equation} (50)^{\frac{1}{4}} \qty(\cos \qty(\frac{\pi}{2 \cdot 4}) + i\sin \qty(\frac{\pi}{2 \cdot 4})) \end{equation}

which is equal to, based on the identities above:

\begin{equation} (50)^{\frac{1}{4}} \qty(\sqrt{\frac{2+\sqrt{2}}{4}} + i\sqrt{\frac{2-\sqrt{2}}{4}}) \end{equation}

Part d

We have:

\begin{equation} \frac{2+2i}{i} \end{equation}

Writing the top and bottom separately in polar, we have:

\begin{equation} \sqrt{8} e^{i \arctan (1)} = \sqrt{8} e^{i \frac{\pi}{4}} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} e^{i \frac{\pi}{2}} \end{equation}

Dividing the two expressions gives:

\begin{equation} \sqrt{8} e^{i -\frac{\pi}{4}} \end{equation}

Taking the square root gives

\begin{equation} (8)^{\frac{1}{4}}e^{i \frac{-\pi}{8}} \end{equation}

Finally, converting the expression back to polar is almost the same as in part C). Recall that:

Recall now that:

\begin{equation} \sin \frac{x}{2} = \sqrt{\frac{1- \cos x}{2}} \end{equation}

and

\begin{equation} \cos \frac{x}{2} = \sqrt{\frac{1+ \cos x}{2}} \end{equation}

Finally, that:

\begin{equation} \sin \frac{\pi}{4} = \cos \frac{\pi}{4} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \end{equation}

Now, notice that:

\begin{equation} (8)^{\frac{1}{4}} \qty(\cos \qty(-\frac{\pi}{2 \cdot 4}) + i\sin \qty(-\frac{\pi}{2 \cdot 4})) \end{equation}

note that \(\sin (-x) = -\sin (x)\), while \(\cos (-x) = \cos (x)\). This results in:

\begin{equation} (8)^{\frac{1}{4}} \qty(\sqrt{\frac{2+\sqrt{2}}{4}} - i\sqrt{\frac{2-\sqrt{2}}{4}}) \end{equation}