Let \(L\) be a regular language; then there is a positive integer \(P\) such that, for all strings \(w \in L\) with \(|w| \geq P\) there is a way to write \(w = x y z\), where…

- \(|y| > 0\) — so \(y \neq \varepsilon\)

- \(|x y | \leq P\)

- for all \(i \geq 0, xy^{i}z \in L\) (where \(y^{i}\) is \(y\) repeated \(i\) times); note that this also means that we can also reduce \(y\) in size to \(y \in \varepsilon\), and it will still hold.

Proof:

let \(M\) be a DFA that recognizes \(L\); and let \(P\) be the number of states in \(M\); let \(w\) be a string where \(w \in L\) and \(|w| \geq P\)

We desire that \(w = xyz\), and has properties

- \(|y| > 0\) — so \(y \neq \varepsilon\)

- \(|x y | \leq P\)

- for all \(i \geq 0, xy^{i}z \in L\) (where \(y^{i}\) is \(y\) repeated \(i\) times); note that this also means that we can also reduce \(y\) in size to \(y \in \varepsilon\), and it will still hold.

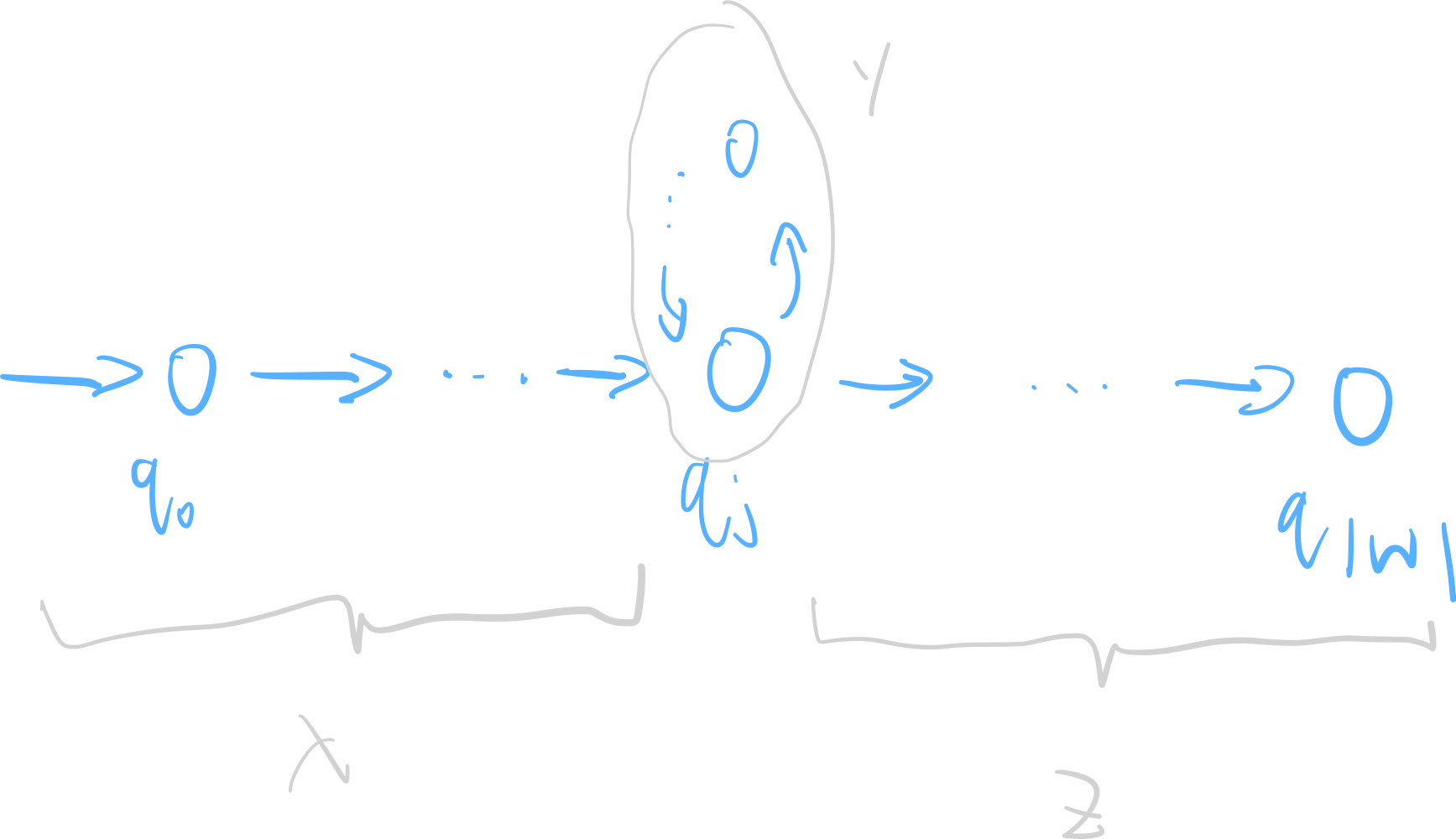

As \(M\) processes \(w\), we will go through at least \(|w|+1\) states (the initial state to the first state is one transition, and since \(w\) has at length \(|w|\), it needs to go through \(|w|\) transitions connecting \(|w|+1\) states; note that \(|w| \geq P\), so the number of states we go through is strictly bigger than \(P\). note that \(P\) is the number of states, so by pigeonhole we go through at least one state twice. Let us call them \(q_{j}, q_{k}\) where \(q_{j} = q_{k}\).

WLOG let’s call \(q_{j}\) and \(q_{k}\) \(q_{j}\) only. Now, let us divide this situation into three strings \(x, y,z\) and verify they have the behavior we desire.

First, since \(0 \leq j < k \leq P\) (that is, \(j\) and \(k\) are distinct due to pidgenhole and the pidgins are distinct), \(y\) (the string that triggers transition between \(j\) and \(k\) ) is nonempty (condition 1). Note that \(|xy| \leq p\) because \(k\) is at most \(p\) because the pigeonhole principle gives us the lack of holes starting at state \(p\) (since, including \(q_{0}\), that’s \(p+1\) states). Since after taking any number of \(y\), you stay at \(q_{j}\); so, you can take \(y\) any number of times, including \(0\) times, to stay at \(q_{j}\) and have the option of moving on.

Generalized Pumping Lemma

Let \(L\) be a regular language; then there is a positive integer \(P\) such that for all strings \(awb \in L\) with \(|w| \geq P\) there is a way to write \(w = xyz\) such that

- \(|y| > 0\) — so \(y \neq \varepsilon\)

- \(|x y | \leq P\)

- for all \(i \geq 0, axy^{i}zb \in L\) (where \(y^{i}\) is \(y\) repeated \(i\) times); note that this also means that we can also reduce \(y\) in size to \(y \in \varepsilon\), and it will still hold.

Example: Using the Pumping Lemma to Show Things is Not Regular

EQ

Suppose we have:

\begin{equation} EQ = \qty {w | N(1) = N(0) } \end{equation}

have that the number of \(1\) in this language is equal to the number of \(0\); we want to show that this is not regular.

Proof:

assume for contradiction \(EQ\) is regular. Let \(P\) be that in the pumping lemma; construct \(w = 0^{P}1^{P}\); note that \(|w| > P\) and it is in \(EQ\). So, let’s follow the pumping lemma and note that there should exist:

\begin{equation} w = xyz \end{equation}

where \(|y| > 0\), \(|xy | \leq P\), and \(xy^{i}z \in EQ\). Note! since \(|xy| \leq P\), the whole of \(xy\) should be all zeros because the first \(P\) part of \(w\) is all zeros. In particular, \(y\) should also be all zeros.

Yet, \(xyyz\) has more zeros than 1s, meaning \(x yy z \not \in EQ\)! We failed the pumping lemma. Having reached contradiction, \(EQ\) is not regular.

SQ

Suppose we haev:

\begin{equation} SQ = \qty {0^{n^{2}} | n \geq 0} \end{equation}

is not regular.

Proof:

assume for contradiction that \(SQ\) is indeed regular. So let \(w = 0^{p^{2}}\) for some \(p\) . Note that we again have by pumping lemma \(w = xyz\) with \(|y| > 0\), and \(|xy| < p\).

This means again that \(xyyz\) should be in \(SQ\). Note that \(|xyyz| = P^{2} + |y|\). Note that from \(|xy | < p\), we have \(0 < |y| \leq P\). Note that \(P^{2} + P < (P+1)^{2}\), meaning that this new string doesn’t actually fit into our language since \(y\) can’t possibly be long enough. Having again reached contradiction, \(SQ\) is not regular.