an is a collection of binary strings such that the minimum between any two codes is some distance \(d\).

This code allows you to correct up to:

- \(t = \left\lfloor \frac{d_{c}-1}{2}\right\rfloor\) one bit errors

- and can detect up to \(d-1\) errors (otherwise we can’t get up to a minimum size codeword

minimum length

what is the largest \(M\) we can have for a code with each codeword of length \(L\) and minimum inter-codeword \(d_{c} = 3\).

This means that we can correct up to \(t = \frac{d_{c}-1}{t} = \frac{3-1}{2} = 1\) one bit of error by taking a nearest-neighbor decoding approach.

To make distinct sequences that satisfy these constants, we need \(M\) codes, each with \(L+1\) possible distinct nearest codewords that can be correctly decoded (\(1\) for the actual codeword, \(L\) for each of the one-bit of error toleration).

This means that we need \(M(L+1) \leq 2^{L}\), because otherwise we can’t make that many distinct sequences. When above is to equality, a code is called a perfect code. This is called the sphere packing bound.

Hamming Code

Hamming Code is a perfect code with \(L = 7\), \(d = 3\); it has \(16\) codewords—meaning it can encode \(4\) bits at a time.

- consider our information sequence with four bits \(b_1, b_2, b_3, b_4\)

- and our codeword computes four parity bits: \(p_1, p_2, p_3, p_4\)

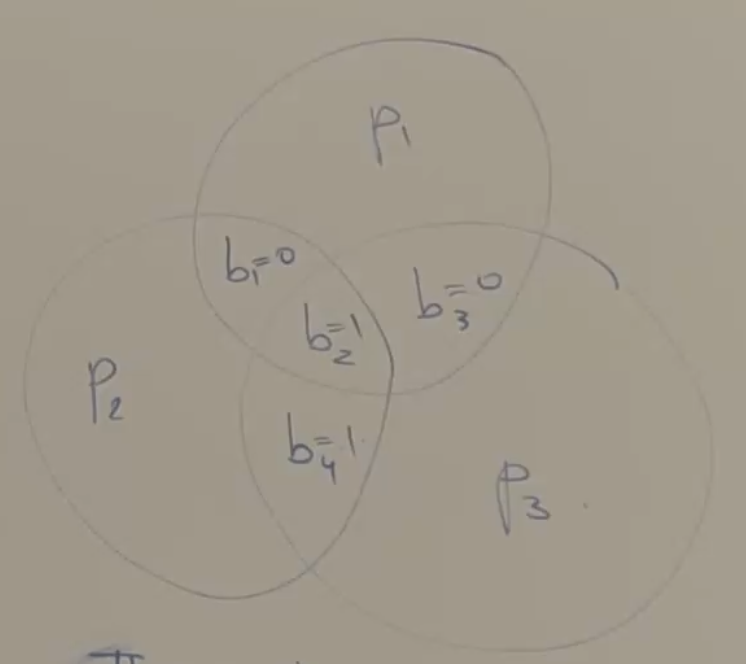

the way that the parity bits are created is by a venn diagram

choose the parity bits such that the total number of 1s in each circle has to be even.

Decoding

ASSUME: there was only one bit flip. Whenever you receive a codeword, return it to the Venn diagram.

- if only one circle is wrong, the parity bit was flipped (because otherwise it should show up elsewhere)

- if two circles are wrong, the data bit between them is wrong

- if all circels are wrong, the middle data bit was wrong

Hamming Code Rate

There exists a Hamming Code for which for all \(M = 2^{k}\) and \(L\) such that the code is satisfied with \(d_{c} = 3\). This makes every hamming code an integer power of \(2\). Remember that a perfect code requires

\begin{equation} M(L+1) = 2^{L} \end{equation}

Which makes:

\begin{equation} 2^{k}(L+1) = 2^{L} \end{equation}

so \(L+1\) must also be a power of \(2\), specifically:

\begin{equation} L+1 = 2^{L-k} \end{equation}

which also gives:

\begin{equation} \log_{2} (L+1) = L-k \end{equation}

specifically \(L-k\) is the number of parity bits for that specific choice of \(L\).

Recall now that \(M = 2^{k}\), so:

\begin{equation} R = \frac{\log_{2}M}{L} = \frac{k}{L} = \frac{L - \log_{2}(L+1)}{L} \end{equation}

This means that rate approaches \(1\) as your code length increases.

Hadamard Code

Create a Hadamard matrix, such that:

\begin{equation} W_{n} = \mqty[W_{n-1} & W_{n-1} \\ W_{n-1} & \~W_{n-1}] \end{equation}

Where \(\tilde{W}\) is the inverse of \(W\).

For instance:

\begin{equation} W_0 = \mqty[0] \end{equation}

and:

\begin{equation} W_{1} = \mqty[0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1] \end{equation}

and

\begin{equation} W_{2} = \mqty[0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0& 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0] \end{equation}

and so fourth. Each row of these matrices is a codeword.

Each row will be the same amount of \(1\) and $0$s. This means that each row is the same distance to all \(0\). Any two codewords is also the same distance away from each other, which is the distance to \(0\).

The size of the Hadamard Code is \(M = 2^{h}\), \(L = 2^{h}\), \(d=2^{h-1}\) where \(h\) is the Hadamard matrix you used.

You will note the rate of this code is quite small:

\begin{equation} R = \frac{h}{2^{h}} \end{equation}

but it can correct a lot of errors:

\begin{equation} t = \frac{2^{h-1}-1}{2} \end{equation}