Because this chapter is not about linear algebra, your instructor may go through it rapidly. You may not be asked to scrutinize all the proofs. Make sure, however, that you at least read and understand the statements of all the results in this chapter—they will be used in later chapters.

So we are not going to go through everything very very carefully. Instead, I’m just going to go through some interesting results at my own leisure. This also means that this note is not very complete.

facts

“you can factor out every root”: \(p(\alpha) = 0 \implies p(z)=(z-\alpha)q(z)\)

fundamental theorem of algebra: “if you have an nth-degree polynomial, you can factor it into n factors” (over the complex numbers, you have as many roots as the degree of the polynomials)

- these coefficients are unique barring ordering

- factoring real polynomials can be treated in two pieces: one piece, the reals, which can be treated usually; then one other piece, the complexes, can be multiplied pairwise together (as over real coeffs they always come in conjugate pairs) into quadratics. This is why all real polynormials can always be factored as \((x-\lambda)(x-\lambda) \dots (x^{2}+ax+b) (x^{2}+ax+b)\dots\)

- the number of complex polynomials has to be even

complex polynomials have \(deg\ p\) factors

real polynomials have \(deg\ p\) real/complex factors, but complex factors come in pairs

we can squish the complex part of the real polynomials together, and get—wlog $m$—first-degree real roots and \(\frac{deg\ p - m}{2}\) second-degree real roots where \(b^{2} < 4c\)

\(x^{2} + bx + c\) has a factor of \((x-\lambda_{1})(x-\lambda_{2})\) under reals \(b^{2} \geq 4c\)

key sequence

complex numbers

- we defined: complex numbers, conjugates, and absolute value

- 9 properties of complexes (see below)

polynomial coefficients

- polynomial coefficients are unique; namely, if a polynomial is the zero function, all of its coefficients have to be \(0\)

division, zero, and factoring

- polynomial division: given two polynomials \(p,s \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\), with \(s\neq 0\), then \(\exists q,r \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\) such that: \(p = s q +r\); that is, given two polynomials, you can always divide one by the other with some remainder as long as the “other” is not \(0\)

- we defined zero (\(p \lambda =0\), then \(\lambda\) is a “zero”) and factor which is some polynomial \(s \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\) for another polynomial \(p\) such that there exists some \(q \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\) such that \(p = s q\)

- we show that each zero corresponds to a factor of the shape \(p(z) = (z-\lambda)q(z)\)

- we show that a polynomial with degree \(m\) has at most \(m\) distinct zeros

FToA and corollaries

- FToA: every non-constant polynomial under the complexes has a zero

- and that means every polynomial over the complexes has a unique factorization \(p(z) = c(z-\lambda_{1})(z-\lambda_{2}) \dots (z-\lambda_{m})\)

- polynomials with zero coefficients have zeros in pairs: if \(\lambda \in \mathbb{C}\) is a factor of the polynomial, so is \(\bar{\lambda}\)

Is a real polynomial factorable?

- A polynomial \(x^{2}+bx+c\) is factorable into \((x-\lambda_{1})(x-\lambda_{2})\) IFF \(b^{2} > 4c\).

- All polynomials over the reals can be factored into at least second degree polynomials

- \(p(z) = c(z-\lambda_{1})(z-\lambda_{2}) \dots (z-\lambda_{m}) \dots (x^{2}+b_{M}x+c_{M})\)

first, review complex numbers

- \(z+\bar{z} = 2 \text{Re}\ z\)

- \(z-\bar{z} =2(\text{Im}\ z)i\)

- \(z\bar{z} = |z|^{2}\)

- \(\bar{x+z} = \bar{w}+\bar{z}\), \(\bar{wz} = \bar{w}\bar{z}\)

- \(\bar{\bar{z}} = z\)

- \(| \text{\{Re,Im\}}\ z| \leq |z|\) both real and imaginary components are smaller than the actual absolute value

- \(|\bar{z}| = |z|\)

- \(|wz| = |w| |z|\)

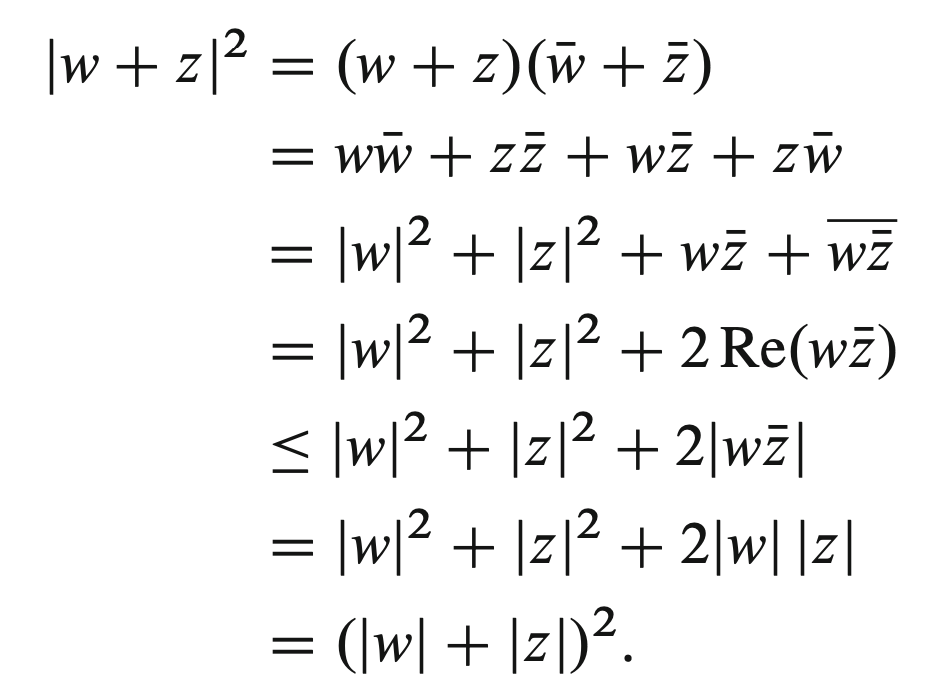

- \(|w+z| \leq |w| + |z|\), the triangle inequality

triangle inequality (complexes)

For \(w, z \in \mathbb{C}\), we do route algebra:

polynomial division

Suppose \(p,s \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F}), s\neq 0\), then, \(\exists\) polynomials \(q,r \in \mathcal{P(\mathbb{F})}\) such that:

\begin{equation} p = s q +r \end{equation}

and \(\deg r < \deg s\).

Proof:

Let: \(n = \deg p\), and \(m = \deg s\). So, if \(n < m\) (i.e. it is not a division), then take \(q=0\) and \(r=p\).

Now, let’s make ???

Factoring

A polynomial \(s \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\) is a factor of \(p \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\) if \(\exists\) \(q \in \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{F})\) such that \(p=s q\).

questions

- proofs: wut

- if the FToA holds, isn’t the polynomials over the reals a “subset”(ish) of the polynomials over the complexes? so there is going to be at least complex roots to all polynormials always no?